At the beginning of the seventeenth century, in the location of today’s park of Richelieu, was located a castle built by the ancestors of the Cardinal, in a place called Richeloc. Attached as he was to the family house where he had passed part of his childhood, Armand Jean du Plessis decided to enlarge the property in about 1625. The former Bishop of Luçon had been promoted to Cardinal in 1622; then in 1624 he entered the King’s service as First Minister. The dwelling of his forebears no longer corresponded to his new situation, and his political rise propelled him to towards an ambitious building project, capable of rivalling the most beautiful residences of his age. Furthermore, he took on the construction of a town on an almost virgin site. After the elevation of the title of the Seigeurie de Richelieu to the status of Duc et Pair in 1631, a distinction accorded to the Cardinal in thanks for his numerous services and in witness of the honour in which he was held, Louis XIII authorised him to create a walled city. The Cardinal invited the population to come and live in his town by announcing numerous privileges, the concession of building plots and the creation of fairs and markets. In addition, the town was to be located on the bank of the river Mable, which would supply the inhabitants with water. A system of sluices allowed the emptying or refilling of both the moats of the castle and the town and this was more or less complete by 1638.

If today the château has been destroyed, the town has remained more or less intact, just as it appeared in the seventeenth century. In contrast to other new towns of the same period (e.g. Charleville and Henrichemont) which have been over-built by later constructions, the town of Richelieu constitutes a unique example of the urbanism of the era. It has retained a complete urban ensemble, very little transformed. Furthermore the town of Richelieu and its château, linked as they are in the same design and both born of the Cardinal’s ambition, show some interesting details with reference to other urban models; both those prior to it and now to contemporary designs. This innovative and ambitious project was inspired by the architecture and spirit of Antiquity. Ancient Rome had become, since the Renaissance, the city of reference. Architects, sculptors and painters were fascinated by this imperial city and by its antique remains.

The town of Richelieu

The works started in 1631 and advanced very quickly. By 1638 the streets were already laid out ; the market hall, the church and the law court were completed. Jacques Lemercier was put in charge of the Cardinal’s project. This brilliant builder was part of a family of Parisian architects and he had completed his apprenticeship in his fathers own office. Architect, engineer and engraver, he was working on the enlargement of the Louvre. After a stay in Rome, he had been in effect been nominated the official architect of the King. At Richelieu it was he who drew up the plans of the town; his brothers Pierre and Nicholas directed the works on site, while the houses themselves were drawn up by master-builder Jean Barbet. The developer-entrepreneur was Jean Thiriot of Paris and the site was under the scrutiny of Henri d’Escoubleau de Sourdis (formerly Bishop of Maillezais and then from 1628 Archbishop of Bordeaux), who kept the Cardinal informed of the progress of the works. He was supported by François du Carroy, steward of the castle, charged in particular with the payment of the workmen. The Grande Rue which runs the length of the town comprises twenty-eight identical mansions, in a classical style typical of the beginning of the 17th century. Each façade is composed of five vertical bays of windows across two levels.

The owners were obliged to make all the façades in the same fashion, as the mansions of the Grand Rue had to be built in conformity to a specification established on the instruction of the Cardinal: house walls and other rubble stone walls rendered, corner stonework and masonry stringcourses of white stone, an imposing carriage door to be surmounted with a pediment, and the mansion roofed in slates. The criteria of unity and regularity, adopted under Henri IV for Parisian squares filled with identical mansions, here found their continuation. But in Richelieu it was applied to mansions built for eminent citizens without any other commercial function. The street level was thus stripped of its boutiques and the covered galleries to shelter them, such a can be seen on Place des Vosges in Paris. Richelieu has also retained its enclosure wall bordered with ditches, and three town gates survive from the original six. Two were situated on the axis of the Grande Rue and four others at the extremities of the two streets at right angles, which cross the two squares. The role of the enclosure wall, inherited from antique and mediaeval towns, is more symbolic than defensive. Ever since Antiquity, ramparts, in addition to their protective functions, gave an impression of strength to their town, which was to be judged from the monumentality of its enclosure and the beauty of its gates.

The town of Richelieu offers something particular and unique for the era: the presence of two squares of equal importance, la place du Marché (the market square) and la place des Religieuses (the nun’s square), and the fact of their being situated at an equal distance from the median rue Traversière (cross street). In the 17th century they were both decorated at their centre point by a fountain and they were then called Place Cardinale and Place Royale respectively. Thus the two fundamentals of French political power, incarnated by Cardinal de Richelieu as First Minister, and Louis XIII as Head of State, seem to have been translated into the plan of the town. However if the two squares are identical, the place du Cardinal was occupied by the church, the market building and the present town hall (originally the law court). Today this square is the still the more lively as many shops are still located there.

The plan of Richelieu is a total break with the ville idéale as conceived in the Renaissance, formed around a centre and organised in accordance with a ‘radio-centric’ spider’s web plan, articulated on the principal of symmetry. In the middle of the 15th century Antonio di Pietro Averlino, known as Filarete (1396-1465) the author of a treatise on architecture, illustrated in a sketch the theory of this type of perfect city, la Sforzinda.

Duality and centrality – Axial perspective

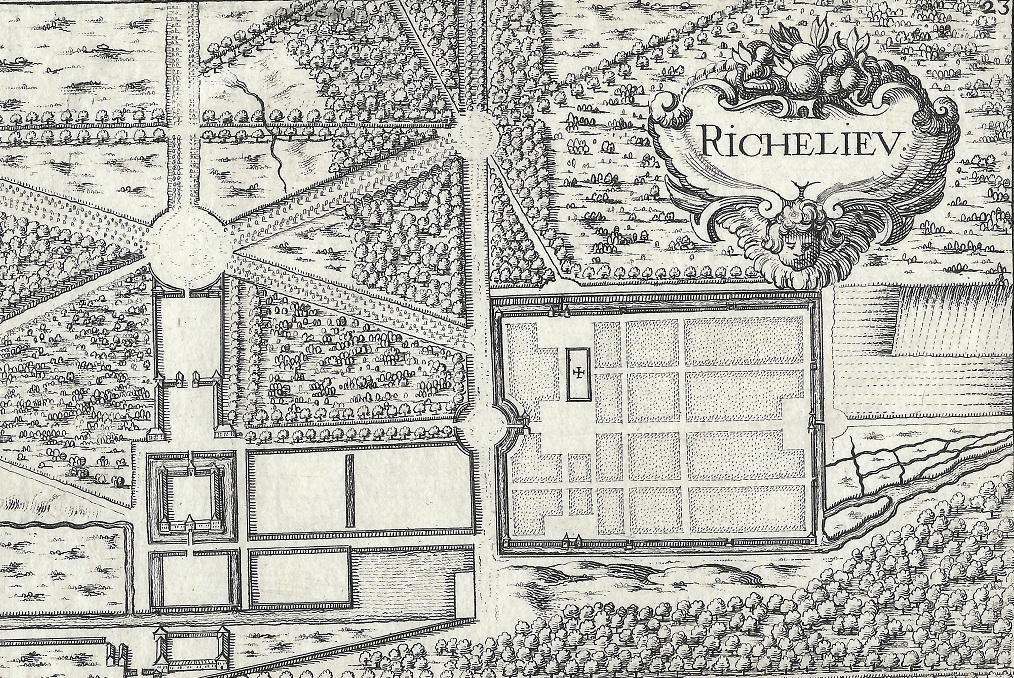

The plan of the town of Richelieu, which is organised around two squares, worried and disorientated the visitors of the period. Richelieu’s unique plan deserves careful consideration. It is elongated and the enclosing wall was pierced by six gates, whereas traditionally there would be only four, each sited facing the four points of the compass.

Richelieu presents in effect a fundamental difference in comparison with previous urban models or to contemporary star-based systems, influenced as they were by the perspectives of the painters of the Renaissance, with a vanishing point onto which all lines converge. The axial perspective, which permits the line of sight to traverse the town from end to end without being obstructed by any obstacle, is an unique aspect of the urbanism of Richelieu. The axial perspective links up with this tradition of Antiquity, and is in contrast to the radio-centric urban models of the Renaissance in which all the lines converge on a single point. Furthermore, axial perspective allowed the symbolic association of the King and his Principal Minister on a single axis, and so to impress on the plan of the town their direct collaboration and their ‘two-headed’ monarchy. Louis XIII had need of a minister fretful of the grandeur of the state, and inversely, Richelieu was nothing without the King himself. So this axiality came to be a sort of ‘ideological’ perspective.

The château of Richelieu

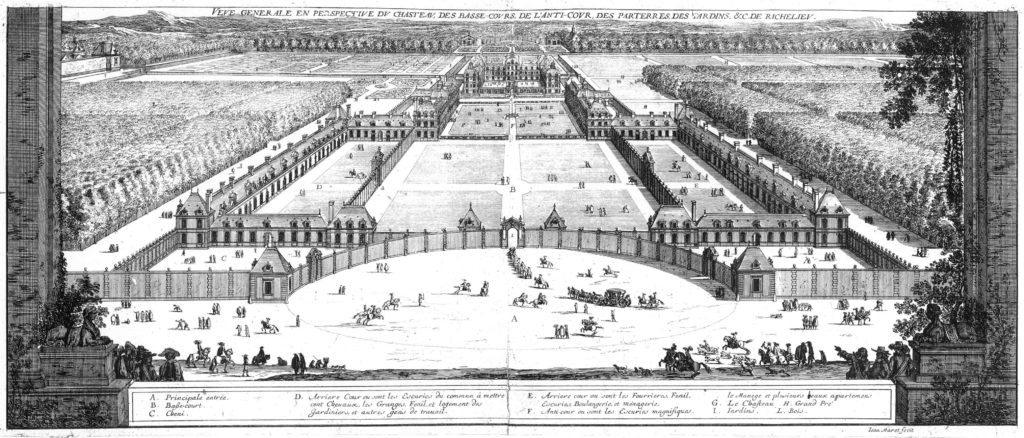

The start of enlargment works on the pre-existing château started from 1625, of which certain rooms were were to be integrated into the new château under the direction of Jean Roger de la Marbelière. Then in 1630 the plans prepared by Jacques Lemercier for the construction of the château de Richelieu were definitively approved by the Cardinal and the construction of the central body of the castle could finally start. The works advanced quickly, from 1636 they continued with the construction of the common works and the grand entry. Architects, painters and sculptors worked actively on the realisation of this marvellous palace. By 1640 the château was almost finished.

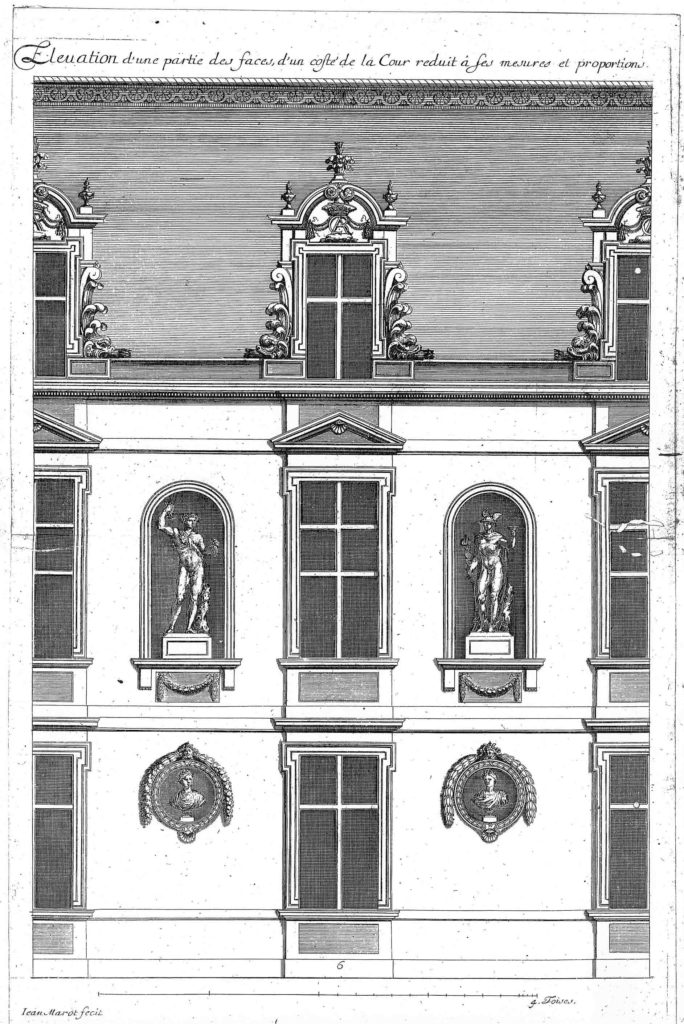

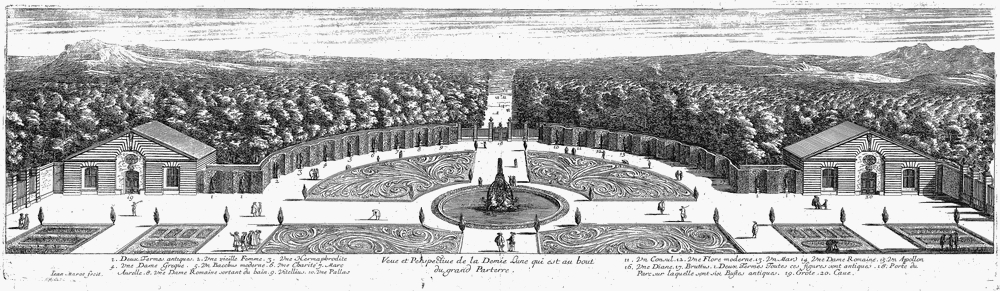

Unfortunately, the château of Richelieu was destroyed in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and in unthinkable conditions… It was bought in 1805 for 153,700 francs by Joseph Alexandre Boutron. He cut it to pieces stone by stone across a period of forty years and dispersed all the furniture and fittings from it. The park itself finished up being subdivided into plot pieces. The château is however well known about as a result of the many plans and engravings (including those of Marot and Pérelle), made after the completion of the château, and also by a very precise seventeenth century description written by B. Vignier, former governor of the château.

The main entry was in the form of a semi-cycle into which arrived three avenues, and located in the West, on the road to Braye-sous-Faye. This entrance, flanked by two pavilions, is one of the few remnants still existing of this magnificent palace. It opened into a vast outer courtyard (avant-cour) 144 metres long, bordered by two back courtyards (arrière-cour) occupied by service buildings of which the stables could house a hundred horses. The narrowerinner courtyard (anti-cour) was flanked by two wings, each including an centrepiece (avant-corps) covered with a dome, and a pavilion at each extremity. The avant-corps of the right-hand wing still exists, now being called The Dome. The main château (the site is today a rose garden) is surrounded by a moat, formed a square of about 80 x 80 metres of which the corners were reinforced.

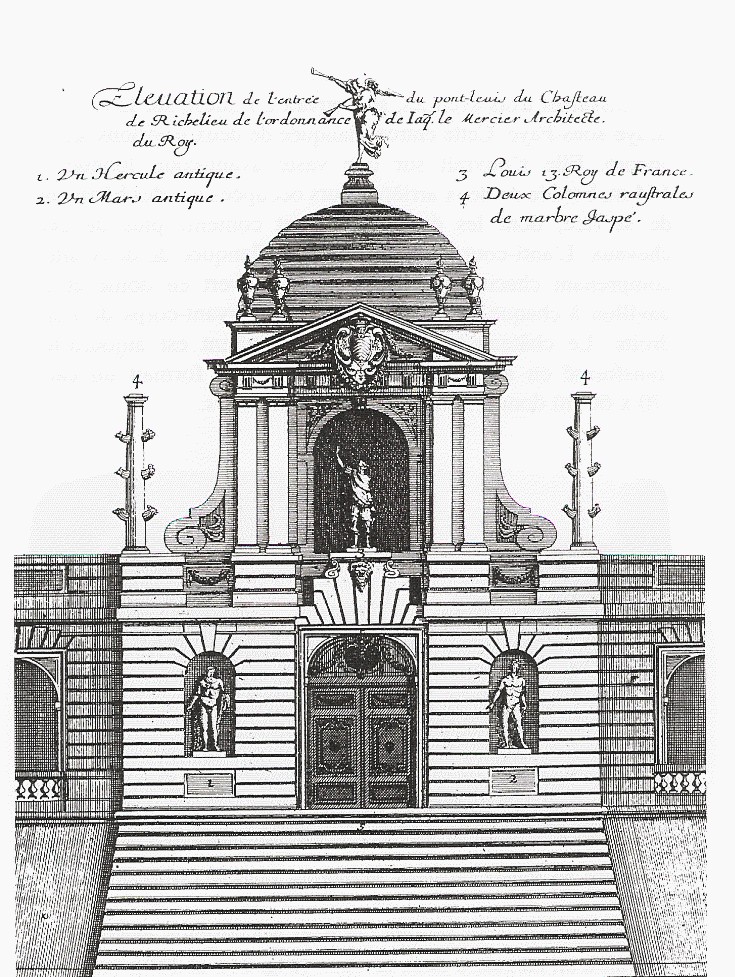

Once the bridge had been crossed, one arrived at a two-level aedicule surmounted by a Renommée (a renown) in bronze, which gave access to the internal château courtyard. At the upper level is a statue of Louis XIII by Gilles Berthelot, flanked by two rostral columns. On the courtyard side, the initials of the Cardinal are inscribed on the metopes: I A D P C D D R (Iean Armand Du Plessis Cardinal Duc de Richelieu). The entry gate-of-honour faced a domed central pavilion situated on far side of the court situated on the same axis, accommodating a monumental staircase, which allowed one access to the main first-floor apartments.

The façades were decorated with sculptures in niches representing Roman divinities and famous Roman emperors. The Cardinal was a great collector. From 1633 he made numerous antiquities arrive from Italy and Greece.

Behind the château stretched out parterres ornamented by antiquities, finishing with a semi-cycle which made an echo of the one at the principal entrance and which was flanked left and right by two ornamented grottos (which still exist today). One is used as the cellar of the château and the other for the orangery. The garden side parterres were cut by a transverse axis, a wide canal fed from the Mable river. Beyond the domesticated nature of the gardens stretched out le parc, traversed by a long allée that extended the entry axis and with it formed a single straight line. The main axis and the transverse canal constitute the main armature of the château; they gave amplitude, equilibrium and majesty to the composition which associated the gardens, the water, and the architecture.

The semi-cycle demarcating the parterres was decorated by antiquities located in the niches in the greenery representing the gods (Bacchus, Pallas, Mars, Apollo, Diana…) and Roman emperors (Marcus Aurelius, Vitellius…). From the semi-cycle, the entry to le parc situated beyond the gardens is formed of triple wrought-iron gates with clear openings.

The château main entry gate pavilion was formed of six pillars each crowned with a bust of one of the six emperors (Augustus, Claudius, Hadrian, Otho, Titus and Drusus). These antiques were situated in the axis of the entry-gate of the château, where on one face there was a statue of Louis XIII and on the other the initials of Cardinal Richelieu. The two-headed power that linked Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu we not simply transposed into the plan of the town. Here, the King and his Minister were again reunited, like two faces of the same medallion. Furthermore the axial perspective arrangement permitted one to directly associate Louis XIII and his Minister with gods and Roman emperors all within a grandiose theatrical setting.

This architectural and iconographic programme has been visibly influenced by Roman architectural models, such as the Theatre of Pompey and the Imperial Fora. Although the systematic excavations of the Theatre of Pompey were not realised until the nineteenth century, it was nonetheless roughly understood by the architects of the Renaissance and of the seventeenth century as a result of the discovery of the Plans of Rome (Forma Urbis Romae) drawn a little after 200 A.D. The plan of the Theatre of Pompey had been conserved and was found among the plan’s fragments in 1542. Furthermore this particular edifice was revolutionary as it was the premier permanent theatre in Rome and is mentioned by numerous historians of Antiquity including Cicero, Pliny and Aulus-Gellius.

This ‘town-park’ evokes the gardens of Antiquity, such as the villa of Hadrian at Tivoli, or the ancient Tibur, and reflects the taste of the ancients for the countryside arranged in an expert way. As at the villa of Hadrian, the château of Richelieu was integrated into a frame of greenery, where the landscape, architecture and water were mixed, and in which were to be the reflections of antique statuary.

© Marie-Pierre Terrien

To know more :

Marie-Pierre Terrien, The Ideal City and the château of Richelieu. An expert architectural conception, Cholet, Editions Pays et Terroirs, 2008 (translated by H. L. Copping)